From Dodger Insider magazine: Hideo Nomo — The Pioneer

A version of this story appeared in a recent issue of Dodger Insider magazine. It is a companion piece to the Los Angeles Dodgers Productions’ “The Story of Nomomania.”

https://medium.com/media/ad2eb3b3ce4fce9bbdfed488d39bba53/href

By Mark Langill

Three decades ago, a pioneer willing to risk everything needed a safe harbor after creating a baseball storm.

His eventual partner in history was a mirror image, someone who embraced a low profile while possessing a steely resolve.

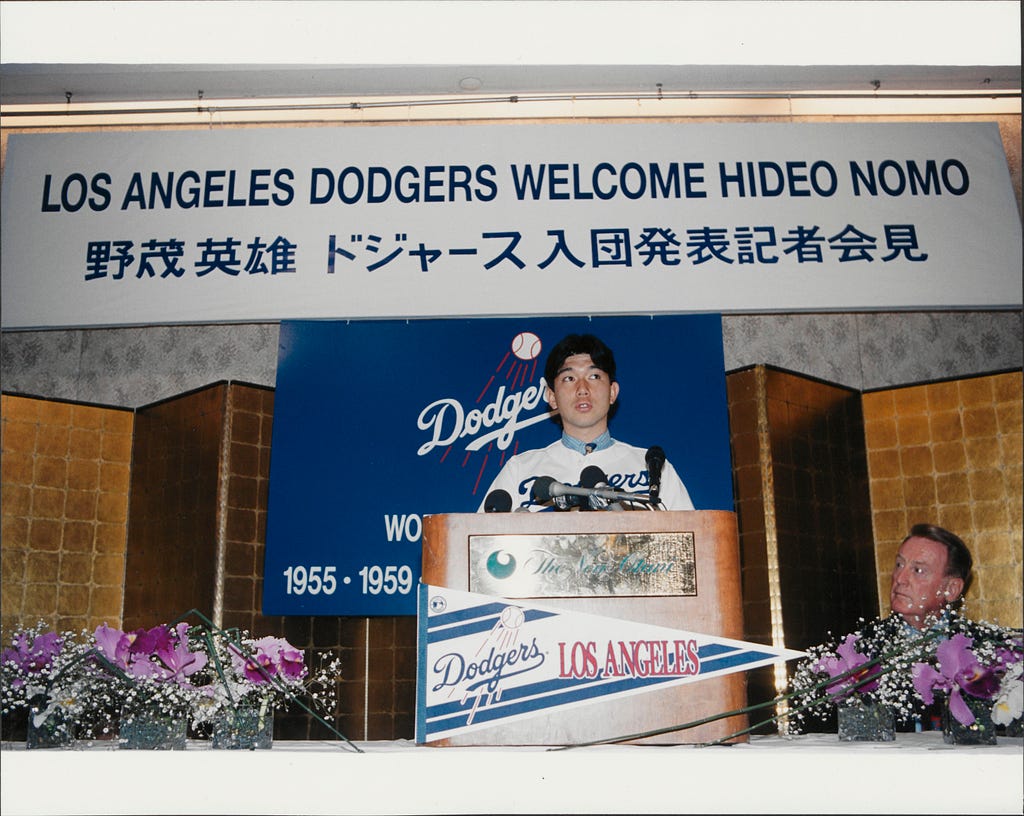

Hideo Nomo and Peter O’Malley didn’t know what the future held when the Japanese star pitcher signed a historic contract with the Dodgers in 1995. But together they created a lasting bond for themselves and a whole new world for Major League Baseball.

After spending five seasons with the Kintetsu Buffaloes of Japan’s Pacific League — which included Rookie of the Year and Pacific League MVP honors in 1990 — Nomo told his agent Don Nomura he wanted to play in the United States in 1995.

Booking a flight to the moon might have been easier. Nomo was still six years away from qualifying for free agency in Japan.

“When I joined Japanese professional baseball and played against Major League players in the Major League Baseball Japan All-Star Series, I realized they were on a different level,” Nomo says. “I wanted to challenge myself at that higher level. So even while playing in Japan, I always had a desire to play in the Majors.”

Nomura studied the history of baseball, specifically, the 1967 labor agreement between MLB and the NPB (Nippon Professional Baseball). In 1964, left-handed pitching prospect Masanori Murakami was sent from Japan’s Nankai Hawks to the San Francisco Giants organization as a “baseball exchange student.” After a solid season at Single-A Fresno, the Giants promoted the 20-year-old to the Majors, triggering a dispute over who owned Murakami’s rights. A compromise was reached in which Murakami pitched for the Giants in 1965 and would return to Japan, where he played until 1982.

During his research, Nomura discovered a loophole. If a player “voluntarily retired” from Japanese baseball, he was technically eligible to play in the Majors. But the player couldn’t voluntarily retire on his own.

After negotiations with Kintetsu officials, Nomo eventually received the offer to “retire” from the Buffaloes.

Unfortunately, the fresh start and a new challenge came at a price. The Japanese media, along with traditional baseball fans in Japan, criticized what they considered a bold decision by Nomo.

Meanwhile, in the United States, a work stoppage by the Major League Baseball Players Association began on Aug. 12, 1994, and eventually wiped out the playoffs and World Series.

Entering 1995, O’Malley and Nomo needed one another.

After getting clearance that Nomo was eligible to play in the Majors, Nomura shopped for his client to the Seattle Mariners, the Giants and the New York Yankees.

The Dodgers, meanwhile, didn’t wait for the phone to ring.

It was the call of a lifetime for O’Malley, who attended the Brooklyn Dodgers’ postseason tour of Japan in 1956 with his sister Terry and his parents, Walter and Kay O’Malley.

Peter O’Malley’s lasting memory of the first of three Dodger postseason tours of Japan — the others were 1966 and 1993 — was first baseman Gil Hodges performing a pantomime act with the crowd in left field, delighting the Japanese fans.

O’Malley marveled at the star players in Japan who were of Major League caliber, and he always thought one day the Dodgers could have a player from Japan.

O’Malley had continued the Dodgers’ international baseball tradition spearheaded by Walter O’Malley, the Brooklyn and Los Angeles team president from 1950 to 1970.

The Yomiuri Giants trained at the team’s Spring Training headquarters in Vero Beach, Florida five times between 1961 and 1981. The Dodgers also hosted the 1984 Olympic baseball tournament at Dodger Stadium.

Nomo had been a member of Team Japan in 1988 during the Olympics in Seoul, South Korea. He pitched against a traveling Major League All-Star team and met several MLB stars at receptions. According to Nomura, Nomo heard compliments like, “You should pitch in the Majors.”

When O’Malley invited Nomo and Nomura to Dodger Stadium, he told other team officials he didn’t want a negotiating session. It turned out that the smallest of details made the biggest difference.

“I told them, ‘I don’t want to talk about money. I don’t want to talk about contract. I just want to talk as a person. I want to know him. I want him to know me and us’” O’Malley said, “And we had a great hour and a half, two-hour meeting, just about life and baseball in Japan in general terms because I wanted him to hear me express my thoughts about the organization and how he would fit in.”

O’Malley asked Nomo if he was available for another meeting the next day. Nomo and Nomura were supposed to leave for New York — a trip they eventually canceled after hearing O’Malley outline how the Dodgers would protect Nomo and let him focus on his pitching.

The rest is history.

Nomo signed a Minor League contract with the Dodgers on February 8, which allowed him to attend Spring Training in Vero Beach, Florida, during the Major League work stoppage that sidelined players on the 40-man roster.

“Once I realized I was going to the U.S. and could play the Majors, I was overjoyed,” Nomo says. “I was excited about the opportunity to compete at a higher level.”

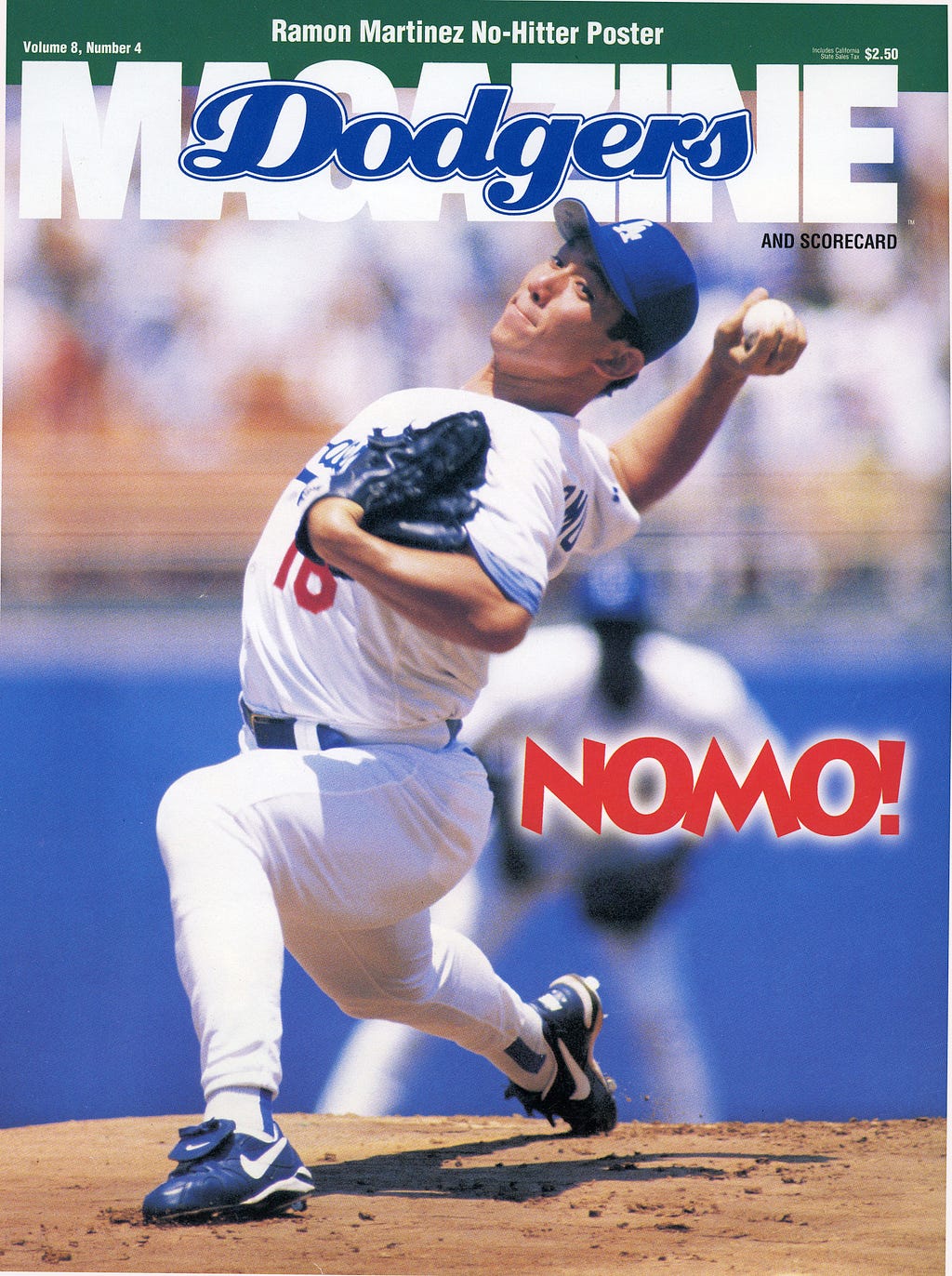

Nomo won National League Rookie of the Year honors in 1995 with a 13–6 record, 2.54 ERA and a league-leading 236 strikeouts in 191 1/3 innings. Nomo struck out 13 or more batters five times in 1995, and he fanned 10 or more in eight games.

In his Major League debut on May 2 at San Francisco, Nomo pitched five scoreless innings against the Giants at Candlestick Park.

On June 2, he notched his first Major League victory, 2–1, against the New York Mets at Dodger Stadium.

On June 14, Nomo set a Dodger single-game rookie record with 16 strikeouts at Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium. He eventually surpassed Don Sutton’s rookie record of 209 strikeouts in 1966.

As the season unfolded, Nomo’s popularity in Japan skyrocketed and NHK-TV broadcast his games on big-screen televisions and screens on streets and buildings in high-traffic areas of 13 Japanese cities.

“I was delighted,” Nomo says. “Having so many fans come to watch, and seeing the stadium erupt when we played well.”

When Nomo was the NL starting pitcher in the All-Star Game, O’Malley told his family he wanted to arrive early at The Ballpark in Arlington, Texas. Without fanfare, O’Malley simply watched Nomo interact with the American League All-Stars during batting practice, as interleague play was two years away.

Nomo became the first National League rookie pitcher to start an All-Star Game since Fernando Valenzuela in 1981. Nomo pitched two scoreless innings against the American League.

“The biggest reason we signed … it wasn’t the Dodgers or Los Angeles,” Nomura said. “It was really Peter O’Malley and how he welcomed Hideo and his wife Kikuko. It’s hard to explain with words … it was like a warm welcoming. It was heart-to-heart.

“Peter certainly understood where Hideo was from and how he had been treated by the media. He was really guarding him to make sure he was happy and to become a successful player. There was a feeling of fatherhood and Hideo decided to stay in Los Angeles.”

Dodgers video producer/editor Aaron Minderhout contributed to this story.

From Dodger Insider magazine: Hideo Nomo — The Pioneer was originally published in Dodger Insider on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.