1965 Championship Year, a Symbolic Game: Got to be perfect

The Dodgers’ eight World Series championships are individually worthy of a movie. With that in mind, we continue with part five of an eight-part series that takes one regular season game — a microcosm game for the team’s championship season — and treat it like a screenplay to a movie. The following is a true story of the 1965 World Series champions. The game is Dodgers vs. Cubs, Sept. 9, 1965.

by Mark Langill and Cary Osborne

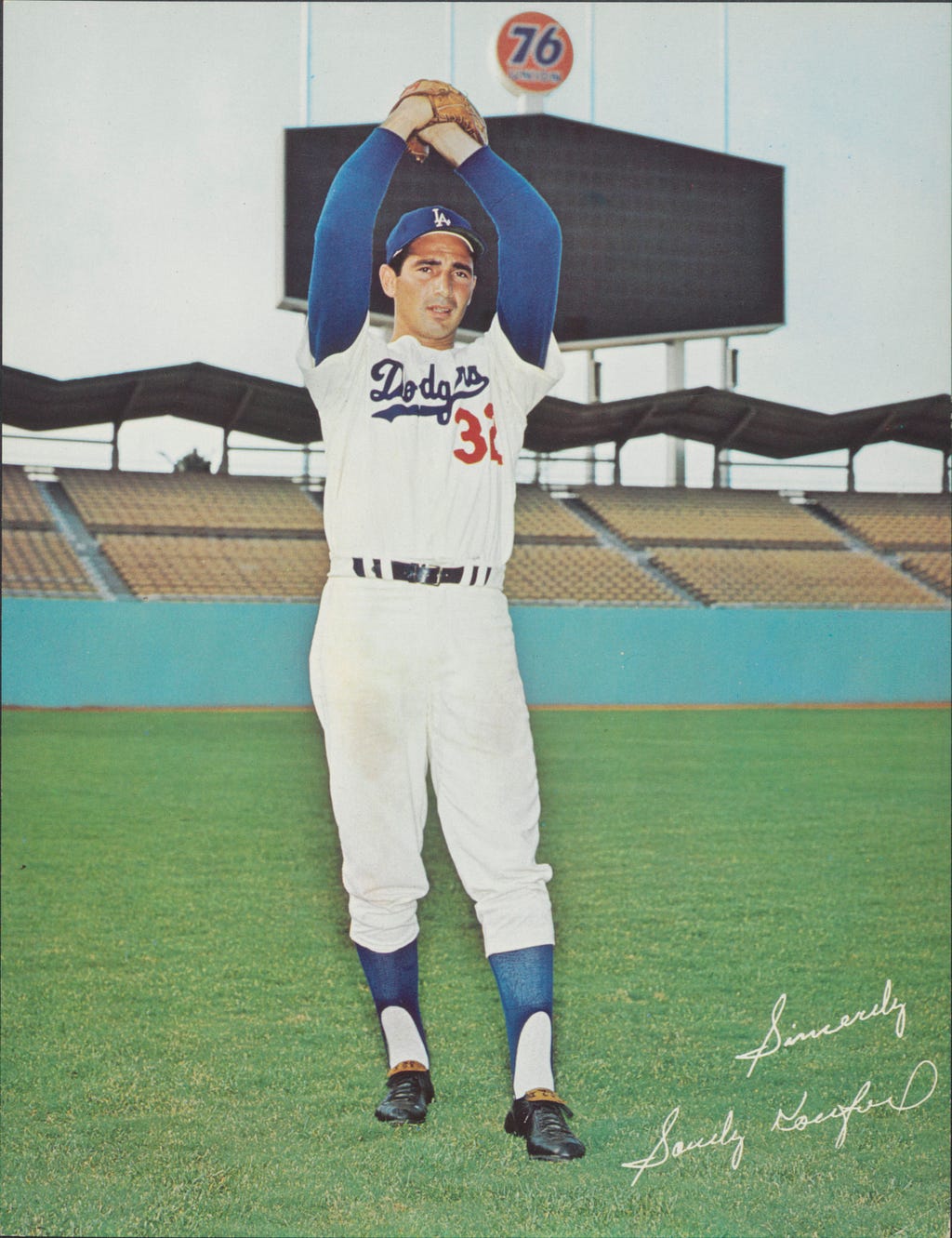

The left arm had been what everyone always talked about. By this point it was fatigued and pained. Not just because of 11 Major League seasons and nearly 2,000 Major League innings, but the eight innings on this Los Angeles evening.

No one talked about his back or his shoulders.

That’s where the weight was distributed on Sept. 9, 1965.

Sandy Koufax walked out to the mound for the ninth inning at a nearly half-full Dodger Stadium, his Dodger blue cap damp from the sweat.

He had carried his team through this game.

The hexagon scoreboard showed a 1–0 Dodgers lead over the Chicago Cubs.

But that was merely the score. Everyone knew the stakes.

It seemed Koufax had accomplished everything in his career, including three no-hitters. Yet his walk onto the field from the home dugout was unchartered territory.

Perfection through eight innings — zero runs allowed, zero hits allowed, no baserunners.

Hitting him on this night was like eating soup with a fork — to borrow a phrase.

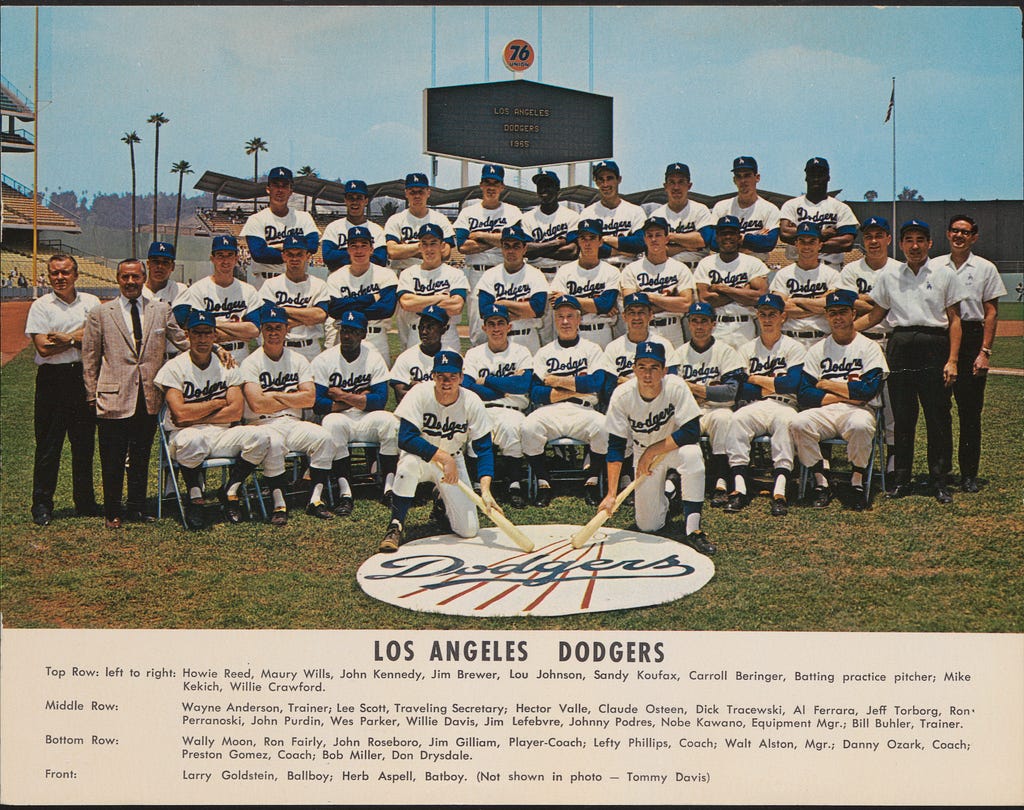

His starting pitching mates — Don Drysdale, Claude Osteen and Johnny Podres — watched from the Dodgers’ dugout. Relievers Ron Perranoski and Jim Brewer from behind a chain-linked fence beyond left field in the Dodger bullpen.

They too carried weight for this team all season, as this was just one of those years where the assembly line that produced runs would often break down.

Tonight, they were weightless watching Koufax.

Koufax dug in on the mound and Chicago catcher Chris Krug dug into the batter’s box.

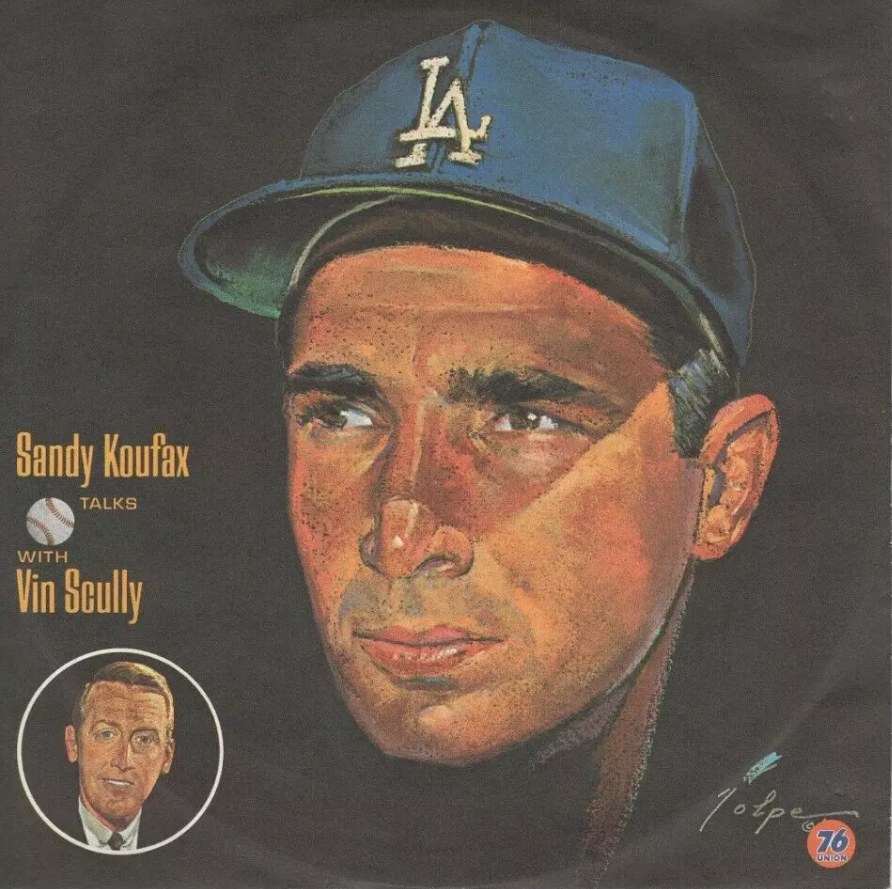

In the broadcasting booth, Vin Scully was ready to cut a record. He called the KFI radio studios to make sure the reel-to-reel tape recorder was rolling for a possible audio time capsule.

Scully’s words were heard in homes but also in the stadium, as fans brought transistor radios to listen to him describe the action they were witnessing.

Scully had watched Koufax’s entire Dodger career, even before his first game in 1955.

Scully was invited in 1954 to watch a hard-throwing prospect try out at Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field. Scully saw Koufax’s back muscles and physique, but he wasn’t sure about his future. What East Coast kid has a West Coast suntan?

A better broadcaster than scout, Scully admitted he took Koufax’s greatness for granted when the prospect became a prodigy.

Now, on Sept. 9, the Dodgers were in a tight pennant race when Koufax entered his start against the Chicago Cubs at Dodger Stadium. The National League standings were bunched at the top with San Francisco, Cincinnati, Los Angeles and Milwaukee within two games of one another.

For the eighth-place Cubs, it was already “Wait ’til next year,” lagging 15 games behind.

Koufax was on the mound in the ninth inning not just seeking perfection, but seeking to ensure his team won.

The pressure.

That mound had claw marks from all the steps and stops from two pitchers going toe-to-toe.

Koufax’s opponent was unheralded left-hander Bob Hendley. Friendly-faced with a flat-top haircut, Hendley was nearly matching Koufax.

Hendley pitched the game of his life, allowing one hit and one walk in eight innings. Both were by Lou Johnson, a journeyman outfielder promoted by the Dodgers in early May when two-time batting champion Tommy Davis dislocated his right ankle while trying to break up a double play at second base.

Johnson was a positive force. People began calling him “Sweet Lou” because of his big smile and kind nature. He was unkind to Hendley’s bid for history this evening.

The only run of the game was scored in the fifth inning. Johnson walked and advanced to second on a sacrifice bunt. On an attempted steal of third base, Krug’s throw sailed into left field and Johnson scampered home.

Meanwhile, Scully mused about a possible double no-hitter since Koufax was unlikely to give up his 1–0 lead. Johnson ruined that possibility with a bloop double down the right-field line with two outs in the seventh.

Scully played it cool for eight innings. The out-of-town scoreboard and regular chit-chat from casual broadcasting disappeared. Scully carefully measured his words. Like writing a letter in fountain pen, he began with the date.

“Three times in his sensational career has Sandy Koufax walked out to the mound to pitch a fateful ninth where he turned in a no-hitter. But tonight, September the ninth, nineteen-hundred and sixty-five, he made the toughest walk of his career, I’m sure, because through eight innings he has pitched a perfect game,” Scully began. “He has struck out 11, he has retired 24 consecutive batters, and the first man he will look at is catcher Chris Krug, big right-hand hitter, flied to second, grounded to short. Dick Tracewski is now at second base and Koufax ready and delivers: curveball for a strike.”

This wasn’t a pitcher looking for a complete game. This felt like Sir Edmund Hillary, a few steps from becoming the first person to reach the summit of Mount Everest.

After Koufax struck out Krug to begin the ninth, two veteran pinch-hitters were next.

Reserve infielder Joe Amalfitano followed Krug. At age 31 in 1965, the former prep star from nearby San Pedro was trying to prolong his career with a lousy team.

Koufax struck out Amalfitano on three pitches.

As he slowly turned and walked back to the dugout, Amalfitano soon approached the next hitter, who wasn’t in a hurry.

Harvey Kuenn, the 1953 American League Rookie of the Year with the Detroit Tigers, no longer was the fresh-faced prospect. The 34-year-old reserve looked a decade older, especially with the plug of chewing tobacco planted in his cheek.

In 1963, Kuenn was the final out of Koufax’s second career no-hitter in 1963 against the Giants at Dodger Stadium, hitting a soft grounder back to Koufax, who threw to first baseman Ron Fairly.

Now, the only domino left to fall, Kuenn had accepted his fate. He looked at Amalfitano. There was really nothing to say.

But baseball players can’t resist a quip, gallows humor that becomes a footnote to the main event.

Crossing paths with the 26th out, Kuenn dead-panned to Amalfitano, “I’ll be right back.”

In the booth, Scully pulled out all his tricks, describing everything from Koufax running his fingers through his hair between pitches to the nervous pacing of Dodger reserve outfielder Al Ferrara in the home dugout.

“It is 9:46 p.m,” Scully began. “… 2-and-2 and count to Harvey Kuenn … one strike away … Sandy into his windup … here’s the pitch … swung on and missed … a perfect game!”

Koufax was mobbed by his teammates on the pitcher’s mound.

“On the scoreboard in right field it is 9:46 p.m. in the City of the Angels, Los Angeles, California. And a crowd of 29,139 just sitting in to see the only pitcher in baseball history to hurl four no-hit, no-run games,” Scully spoke into his microphone, five floors up from the field. “He has done it four straight years, and now he caps it: On his fourth no-hitter he made it a perfect game. And Sandy Koufax, whose name will always remind you of strikeouts, did it with a flourish. He struck out the last six consecutive batters. So, when he wrote his name in capital letters in the record books, that “K” stands out even more than the O-U-F-A-X.”

In the clubhouse, someone had the idea to have Koufax pose with four baseballs in front of photographers. Two in each hand, each with a large zero written in black shoe polish.

As the party subsided and the players showered and dressed to go home, nothing had really changed — at least in the standings. The Dodgers were still tied for second place with Cincinnati, a half-game behind San Francisco.

For his fans and teammates clinging to Koufax’s left arm, there was no margin for error with three weeks left in the regular season.

Koufax would have to remain close to perfect. And then, if the Dodgers get there, likely stay that way in the 1965 World Series.

1965 Championship year, A Symbolic Game: Got to be perfect was originally published in Dodger Insider on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.